Previously, I wrote a long article about our family’s move to sunny Nelson and our first steps settling into our new life. After the article was published, I received a lot of questions. People asked about life in Nelson, studying at NMIT, language skills, children’s adaptation, prices, and the weather. But most of the questions focused on two main topics:

- Is it hard to study in Level 8 and 9 programs?

- Is it possible to find a job in Nelson?

So in this second article, I’ll try to focus primarily on these two topics. I’ll explain how the study process is organized here, what coursework is like, and which skills help students complete their assignments. I’ll also share what kind of part-time job I was able to find early on, and the conclusions I’ve come to during my job search.

Finally, I’ll say a few words about my volunteer activities and why volunteering is so popular in New Zealand.

Content

Winter in Nelson

But first, let’s start with the fact that winter has arrived.

Before the move, we had read a lot about New Zealand’s mild and rainy winters, which, as it turns out, are more typical of the North Island. On the South Island, winter is different: most days are sunny and warm, but in the evening it gets noticeably colder, and by morning, temperatures can drop to zero or even below.

That wouldn’t be such a problem if the houses here were better equipped for cold weather. I’m sure many people have heard that New Zealand homes are cold and uncomfortable in winter, but I’d rather express it in numbers: at night, the temperature in our house drops to 10–11°C.

Typical house in New Zealand during winter period

There are dozens of ways to keep warm here. For example, electric heaters, fireplaces, wood burners, electric blankets, hot water bottles, pajamas, extra layers of bedding, and window insulation films.

A heat pump (an air conditioner that also heats) helps quickly warm the air, but with single-glazed windows and hollow walls, the heat escapes very fast. Leaving heaters on overnight is an expensive pleasure. We rarely do it, and still our electricity bill comes to NZ$200.

You have to change your habits. You can’t walk around in shorts or sleep in just underwear anymore. Of course, there are warmer houses, properly constructed for winter time, and hopefully you’ll be lucky enough to find one of those.

As I mentioned in my first article, we’ve been luckier with good people. For example, one of my classmates, a local born in New Zealand, originally from Scotland—heard that we were cold and brought us a bunch of blankets, throws, and warm clothes. He said he was embarrassed that landlords rent out cold houses that can ruin a person’s impression of the country.

Other kind people gifted us a great TV, and we even found a working scanner on the street with a note saying: “It works, please take and use.”

So the small everyday hardships are more than compensated by the warmth and kindness of Nelson’s residents.

Studying process at NMIT: Course structure and assignments

Now, about whether studying is hard. There’s no simple answer to this. It depends on the subject, the tutor, the student’s level of English, personal strengths, and prior experience. That’s why I’ll try to describe my program at NMIT using clear facts and concrete examples instead of just my subjective opinion—so each reader can decide for themselves whether it’s difficult or not.

It’s like talking about room temperature. You can say it’s “a bit chilly,” or you can say “10 degrees.” I think we all know which is more informative.

Moreover, the quality and speed of completing assignments depends heavily on specific skills. Especially the ability to read and write academic texts quickly. If you have the chance, I strongly recommend practicing those skills before your studies begin. Personally, I didn’t really look into the curriculum beforehand, and some aspects, like the volume of assignments, came as a surprise.

My program, Master of Applied Management, consists of 8 courses and a final dissertation. Each course runs for 8 weeks and the academic year is divided into 4 semesters, meaning you take 2 courses in parallel per semester. Each course has just one 4-hour class per week with the tutor. All other time is for self-study. During class, tutors introduce the weekly topic, cover the key ideas, and sometimes give short tasks for small group discussions.

In general, tutors here don’t spoon-feed the material. Instead, they point you in the right direction and expect you to explore the topic independently.

Занятие в аудитории NMIT

Course work and assessment

Each topic comes with a list of required and recommended readings. Mostly academic articles and textbook chapters. Over the course of the week, students are expected to study these materials, participate in online forums, or work on group assignments.

So, a typical study week may feel quite relaxed—but everything changes when the deadlines for major assignments start to approach.

Each course includes three assessments, which make up the final grade. The first assignment is usually theoretical. Most often, it’s a research-based academic essay on a given topic, using both recommended readings and self-sourced materials.

In most cases, students are expected to include at least 10 reliable sources, with 20 or more being the benchmark for a high grade. The quality and complexity of these articles varies. Some are written in relatively accessible language, while others are quite difficult to read.

For example, this is a fragment from an article written in dry academic style (from the course Strategic Marketing):

And here is an example of a more approachable academic text (from the course Leadership and Managing Talent):

There are dozens of such articles, and reading them is one of the most time-consuming parts of the study process. That’s why the skill of scanning texts is crucial. Reading diagonally and quickly identifying the core ideas that can be used in your own work. There are many open-access guides on how to read academic texts effectively. I highly recommend reviewing them. In my first semester, I used to read everything word for word, like a novel. Don’t make that mistake.

The expected length of the essay is usually around 3,000 words. The assignment is assessed based on its structure, logic, coherence, and clarity. A lot of attention is paid to academic writing style, grammar, and correct referencing.

Who marks the work also plays a role. There are two possible scenarios:

- Sometimes, the tutor marks the work. In my experience, this often results in a higher grade, as tutors are usually short on time and provide brief feedback.

- Other times, an external marker is brought in. Someone hired to grade impartially. This is when your work is judged far more strictly. Even minor mistakes in referencing can lead to point deductions, and the marker usually leaves detailed comments.

This emphasis on academic precision over practical application can be frustrating for many students. Based on my observations, this tends to happen when the tutor has little or no real-world business experience.

Here’s an example of my own writing that was graded quite highly by a marker (from the course Leadership and Managing Talent):

How much time it takes to find sources, read them, and write the essay varies greatly by person. For me, it takes about five part-time days, or around 30 hours. Even now, my English is far from perfect. Although I scored 94/120 on the TOEFL, I initially struggled to write and speak fluently with native speakers. I had a noticeable lack of regular conversational practice.

Presentation-Based Assignment

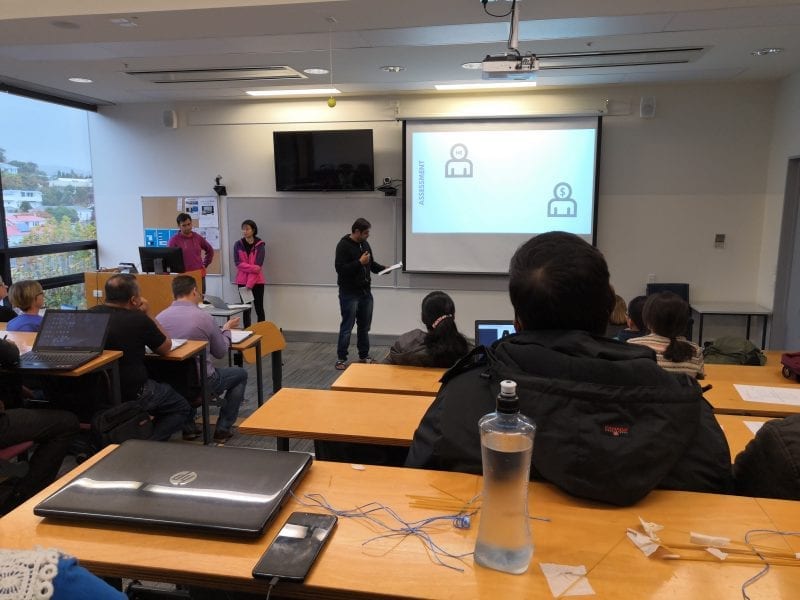

The second assignment is usually a presentation, either individual or group-based. You need to research a given topic, prepare a presentation, deliver it in class, and answer questions from the audience.

Here, skills in public speaking and working with presentation software come in handy. You’re evaluated on your slide design, engagement with the audience, fluency, persuasiveness, and energy.

Personally, I enjoy group projects more. First, they provide language practice; second, you get used to working with people from different cultural backgrounds.

For instance, I had a partner from India who didn’t quite grasp the idea of deadlines. I had to use all my skills in persuasion and emotional control.

Sometimes, our group discussions would get sidetracked—once, someone asked me what I had for breakfast. But all of this is a valuable exercise in Cultural Intelligence.

Presentations at NMIT

Final Assignment

The third assignment is usually the culmination of the course. It’s more practical—you’re required to apply the course theory to a real-world scenario. This could involve:

- Developing a strategy for a real company

- Creating your own business project

- Writing a consulting report based on a case study

All the usual academic standards for writing and referencing still apply. The word count is typically around 4,000 words.

These assignments take even more time, but personally, I find them far more interesting than writing essays. First, the connection to real life is more obvious; second, there’s more room for independent thinking.

Although, for some people, these are the hardest types of assignments—it’s all very individual.

The only thing that concerns me is that eight weeks for a full course isn’t much time to gain deep enough knowledge to produce a high-quality, applicable project.

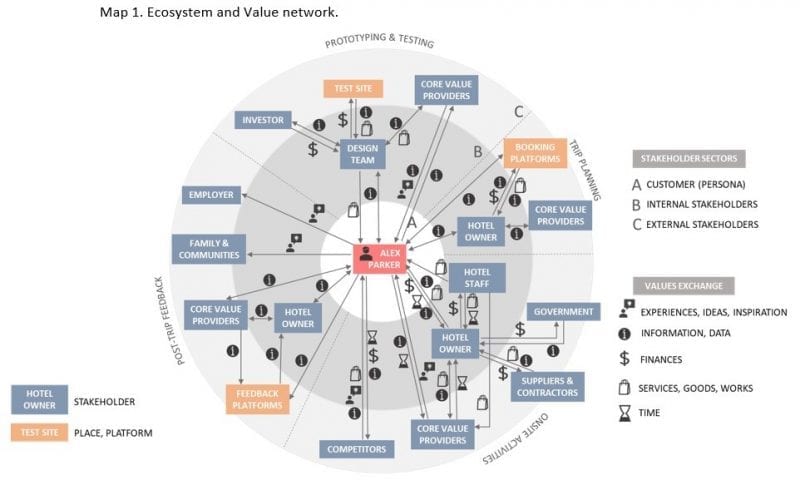

As an example of a creative thinking task, here’s a business ecosystem map I developed for my own project (from the course Design Thinking and Entrepreneurship):

Grading System

All assignments are graded on a 100-point scale. Anything above 50 is considered a pass, while a score above 90 is quite rare. If your overall score for the course is below 50, it’s considered a fail. However, even in that case, you are usually allowed to resubmit some of the assignments—and in most cases, more than once.

So, most of the study process boils down to reading and writing. Each course typically requires students to produce around 8,000 to 10,000 words, and if you add up all the courses and the final dissertation, you get around 100,000 words. Roughly the same as Volume I of War and Peace.

That was quite a detailed overview of the academic side, but I hope it now helps you evaluate how much time is needed to complete assignments, what level of English is required to keep up, and how much time remains for leisure, family, hobbies, and work.

Job hunting

I started looking for work toward the end of my first semester, once I had a better understanding of how demanding my studies would be. I decided to base my job search on my professional experience in the event industry. I had worked for many years organizing B2B exhibitions, and I also spent two years preparing the stadium in Saransk for the World Cup.

Naturally, I brought a complete portfolio of references, certificates, and letters of appreciation. But spoiler alert: none of it mattered here. People have heard about what’s going on in Russia, but it’s like they hear it from the moon—this is truly a different world.

I searched for job openings mainly on seek.co.nz and trademe.co.nz. Over about two months of active searching, I came across only three positions that directly matched my qualifications.

- The first employer rejected me due to overqualification. They didn’t believe someone with my background would stick around long for a part-time job with a modest salary.

- The second turned me down after learning I was a student.

In New Zealand, students are legally limited to 20 work hours per week, and event work usually involves irregular hours.

Employers generally avoid hiring students for jobs where staff turnover is undesirable. They know full well that after graduation, students will be looking for full-time roles and higher positions.

As a result, most students here work in retail (cashiering, stocking shelves, or sales if language skills allow), cleaning services, or pizza delivery. Permanent roles go to people with a more predictable personal situation and clear long-term plans.

I also noticed that in interviews, employers pay much more attention to whether they “get” the candidate as a person, rather than just their resume. It feels more like they’re choosing a family member, not hiring a specialist. I’m not sure if this is the case across all of New Zealand, but in smaller towns like Nelson, it definitely is—and that’s something to be aware of.

The third position I applied for ended the same way: the full-time job went to someone with no study obligations, and I was offered temporary contract work. That’s what I’m currently doing—helping to set up venues for sporting and concert events.

Interesting that the venue where they regularly hold basketball games and more than 50 events per year employs only three staff: a manager, a coordinator, and a multi-skilled technician. In Russia, the same venue would probably employ 20–30 people, half of them in management.

Here, even managers will do manual work like lifting, assembling, and transporting equipment. Personally, I find this system more efficient and human. Back in my management days, I never avoided getting hands-on. It builds a stronger connection with your team and lets you understand the business from the inside.

Basketball game at Nelson Trafalgar Centre

If You Want a Job Quickly…

If you’re looking for a job and want quick results, here are two key tips:

- Simplify.

Be ready to start from the bottom—even below the level where you began your career.

Think about what you can do with your hands and mind right now. Be clear and concise when describing your skills, and back them up with examples.

Show that you are motivated and enthusiastic, not desperate.

People here, regardless of their field, generally enjoy their work.

Of course, keep applying for more qualified roles—but don’t expect instant success. - Adapt culturally.

Despite New Zealand’s focus on diversity, equality, and inclusion, there is a dominant mainstream culture—and you need to fit in.

Be observant, learn the unspoken norms, and blend in. Some people manage this quickly; others struggle. Some people resist entirely, emphasizing their own cultural identity—but that makes adapting much harder. If you approach things with an open mind, there are ways to speed up your integration, and one of the best is through volunteering

Volunteering

Volunteering is hugely popular in New Zealand. Some organizations are almost entirely staffed by volunteers. Local volunteer centers offer dozens of options in social, educational, environmental, and cultural sectors. As a big fan of nature, I chose to volunteer at the Brook Waimarama Sanctuary.

Me volunteering at Brook Waimarama Sanctuary

This is an “ecological island” surrounded by kilometers of fencing to keep out introduced predators (mostly rodents). The goal is to restore and protect New Zealand’s unique flora and fauna, especially native bird populations.

The sanctuary is open to the public and has many hiking trails. Once a week, I help maintain these tracks—trimming overgrown plants, clearing leaves, and cutting fallen branches. Working outdoors with birds singing around you feels like a reward after writing yet another academic essay.

The volunteer team is mostly made up of retirees, and to my surprise, these people in their 70s and 80s are in amazing physical shape. They climb hills, cross streams, and work 5–6 hours straight like it’s nothing. It’s incredible how regular physical activity boosts and extends quality of life. People here understand this well. And that’s why there’s never a shortage of volunteers.

Volunteer crossing a mountain stream at Brook Waimarama Sanctuary

During breaks, we chat about cultural differences, politics, and education systems. Once we talked about literature, and I was amazed how well they knew Russian classics. I’ve also met people in my squash club who were familiar with Russian history and culture. Though, of course, most often they ask about cold weather and Putin, not ballet and space.

Several people even shared stories of traveling in Russia. One adventurer told me about his bike trip through Siberia and the Russian Far East—despite also having visited both poles and climbed Everest. He said it was the hardest expedition of his life, tougher than swimming to the North Pole through the Arctic Ocean.

So the stereotype that Kiwis care only about sheep is just a myth. Just like anywhere else—it all depends on the people and your circle of communication.

Read about volunteering New Zealand

Family

Our kids are doing well. Adaptation has gone smoothly. Our daughter is often invited to birthday parties by her friends from kindergarten. Birthdays here are big events, with entertainers or fun programs organized by the parents themselves. Adults are always present too—it’s a great way to get to know other families. In a sense, kindergarten here is also a community.

Children at a birthday party

Our older child is also enjoying school. I know that many parents from Russia worry that kids in Russian schools gain more academic knowledge than those in New Zealand. And that’s partly true—schools here don’t aim to stuff kids’ heads with information on every subject. Instead, they focus on tools, methods, and teaching kids to think independently.

In my view, that’s a much better approach, especially in today’s world, where access to information is everywhere, and the real value lies in how to work with it.

It’s surprising when people who went to school decades ago still expect the education system to use the same outdated methods. Personally, I believe that the Russian education system is obsolete, no longer in demand globally, and in need of reform.

My wife has completed her English courses and is also starting to look for work. We’ve got a few interesting ideas and will be working to bring them to life. Of course, language learning doesn’t stop, so we try to communicate as much as possible in English every day.

And of course, I can’t skip mentioning our travels around the island. As soon as you leave the city, you forget all your worries. We’ve been gradually increasing our trip distances, and the kids are getting used to mountain roads and long drives.

Our family on a trip around the South Island

Recently, we visited Kaikoura—a popular tourist spot where you can see whales in the open sea or watch fur seals lounging on coastal rocks. If you’re careful, you can get surprisingly close to them.

Fur seals on the east coast of the South Island

We also made it to Wharariki Beach, the northernmost point of the South Island. It was so windy we could barely stay on our feet. Many of you might recognize these views as they’ve been featured as default Windows wallpapers.

Battling the wind at Wharariki Beach

Also, we dream of camping out in these beautiful places for several days. And the best part is our dream is now within reach.

Landscape of the South Island

This is the end of our second story about life in Nelson. If you have any questions, I’ll be happy to answer and share what I know. You can reach me on Facebook.